The first words of this history are rather stark. "Posterity would regard as 'fiction' the circumstances under which Americans achieved victory in the War for Independence. So wrote General George Washington as the conflict was drawing to a close." And then she went on to prove exactly why this proposition made sense to the General.

Erna Risch, the pre-eminent Logistics Historian of the United States Army, opens her magnum opus, the grand narrative of every aspect of supply in the War for Independence with this dose of mystified and cynical reflection upon success. For the story of logistics for the forces that won independence from British rule was one of continued and ritual struggle. And not for want of resources. America was a rich land, the Colonies largely prosperous in their economies. No, the failures were logistical, from political to tactical. In this work, Risch details them all.

Logically, her work on the first war came last in her career. The mastery of the full history was needed to make comprehensible the more limited period. She came out of retirement after over a decade at the Bicentennial to pen this work. Having spent considerable time through her career with the Army detailing the Quartermaster in its service during the Revolutionary period and the logistical enterprise of the Republic, as well as mastering the enormity of WWII, she was the logical choice. In five years, 1981, she published a work of detail and clarity, in both evidence and analysis.

Supplying Washington’s Army is the history of the Continental Army and its support and supply in the war. It narrates the origins of the logistical systems to manage the challenges – the lack of political clarity in the administration of war – but demonstrates throughout how this flaw continued, nevertheless, to define the travails faced throughout. To do so, she importantly situates Washington’s command at the start of the war within the “States,” their militia, and the Sunshine Patriots. The initial recourse to ad hockery fails on its own merits, but left in its wake unanswered problems of politics and infrastructure. Regularization of military administration was demanded early and with vehemence through the first years of the war to meet the needs, and structure and processes ensue. Ironically in this moment, as we have resisted the bureaucratic truth from the start. Nevertheless, as the tale is told, the irreconcilable political limitations would continue to hamper the war effort throughout and victory was achieved despite logistical failings.

To set the scene, she first draws the picture of the terms of logistical collapse suffusing the Continental Army in the early years. The basis of the original system was the co-optation of the operation of local merchant. As the militias had been drawn from neighboring localities around Boston, the support was similarly arranged. The merchant had real skills and knowledge, they functioned within the mercantilist system as shipper, banker, wholesaler, retailer, warehouseman, and insurer, arranging each by contract as needed. Amazon only changed the means of communication – the model is ancient. Ultimately, these men of skill as well as others of character would be organized within administrative organizations to manage military supply. But unregulated private and contracted supply could not meet the needs of the Army. Nor could the Continental political-economy. The financial-economic condition as much as the military process and structure harmed the work to supply the Army. Various modes of drawing the resources from the new nation never fully sufficed to sustain or manage the financial condition of the Colonies. This is the context within which supply of the Continental Army occurred.

The work is too great and detailed to cover here. We will dally here in one area, transportation – most vexing – to provide the contours of the issues facing the enterprise of supply. However, in its delightful official publication fashion, the Table of Contents is detailed to the sub-heading, and outline for the reader. And from the discussion of transport woes, the shape of the broader logistical problems emerges.

In this day of rapid transportation, it is difficult to appreciate the slowness of 18th century travel.

In her several chapters on transport Risch covers the myriad issues confronting transport that similarly plague the entire logistical operation. And across the years, theatres, and phases of organization attempted by the political and military authorities, transportation was an irresolvable hurdle to supply.

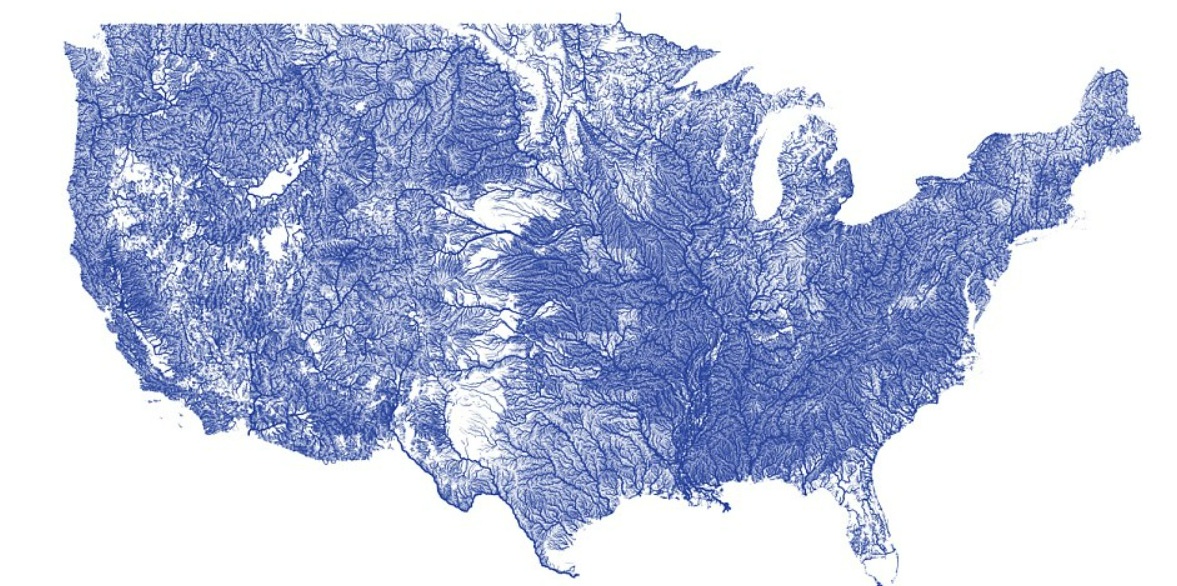

First, she deals with the scale of the war theatre. In an age of slow transport, the territory of the Americans at war stretched from Massachusetts to Georgia, facing an agile maritime opponent capable of landing anywhere. Tyranny of terrain and strategy was the first challenge of transportation. [1] The North/South routes had once been covered at sea, East/West by river and trail. The Royal Navy blocked the former, and the latter had limited utility to the campaigning. Left to struggle along webs of town-to-town routes, or forge new paths to ford the myriad waters along the east coast. Thus, despite ample food throughout the colonies, getting it to where the army needed it was a usually insuperable challenge. The Noble Train of Artillery, an epic battle to move cannons from distant forts was among the exceptions to prove the rule. At the other end, Benedict Arnold’s expedition to Canada died by supply in the same way Braddock’s did a war earlier.

Corruption and ineffectiveness of the processes and structures were another category of problem. Relying upon private enterprise, contracted transport waggoneers would pour off the brine from the salt beef to save the horses and starve the army. [2] The overlapping systems dragged on each other. The horses needed to move goods and the Army themselves required supply of forage and related materials. Shortages of the resources to run the engines of war – fuels and raw materials – weakened the army at every turn. Of the fuel demands to move the Army and its baggage trains, the forage work for the horses and oxen never ended.

Further beleaguering every point of the chain throughout the were the financing problems of a weak political authority and the economic struggle of a relatively useless currency, the Continental Dollar. The sole authority convened to organize the collective fight against the British was never vested with sufficient power to demand taxes – too Whiggish by half on this matter, the individual States refused to relent on the matter. The Continental Congress could ask for drafts of money or goods from the States, but could not force. Interestingly, the weak representatives did frequently try to pass off Impressment of materiel onto the Army as a means to obtain horses or other transport needs for the army. Washington, however, would not be the face of such acts and brought along civilian legal authority to impose the edicts enabling forced collection. [3] Complicating any funding was the ever decreasingly valuable war-time currency. Much of the work to support the Army was contracted, whether in purchases of goods, services, or war materiel, and the instability of the Continental Dollar befouled the work. [4] So even as administration improved, the ability to pay and the costs continued the logistical struggle year on year.

Risch progresses in this way through the travails in each major category or topic of supply. And yet at the end, as she nevertheless continues to throw down illustrative examples, the assessment throughout that logistics shaped, but did not determine any battle or campaign, and clearly not the war stands. This is an important point. Much is made that capable logistics are critical to strategy. The correct response to that is “yes comma but”. Logistics are relative and strategy must take account of reality. Therefore, logistics capability and capacity do not define who wins or loses – the North Vietnamese famously had so little supply flowing along the Ho Chi Minh Trail that the bombing campaign could not effectively target it. Instead, logistics interacts with strategy as each tries to take account of the economics, society, and politics. The party that best matches strategy to logistics and the civilian triad invariable wins.

This understanding of the role of logistics in war matters as a critical piece of understanding now more than ever. Where pure or perfect mass is insufficient on its own if applied poorly, the strategic ineffectiveness of the US in the post-WWII era at many turns makes sense. The Colonists’ defeat of the British in the War for Independence becomes politically and strategically arguable. And the theory of victory in Ukraine can withstand American perfidy.

Notes

[1] Pp. 33-6; 64-5.

[2] Pp. 83-5.

[3] Pp. 72-3. Washington’s deference to civilian authority was particularly evident in matters which pitted the army against the civilian population. The recognition of the “delicacy which your Excellency has ever observed with Respect to the Civil Power of this State,” earned him the “Warmest Acknowledgements” from the New York Committee of Safety. (Letter from the New York Committee of Safety, 23 November 1776, Papers, V. 7, p. 200.)

[4] 85-6.